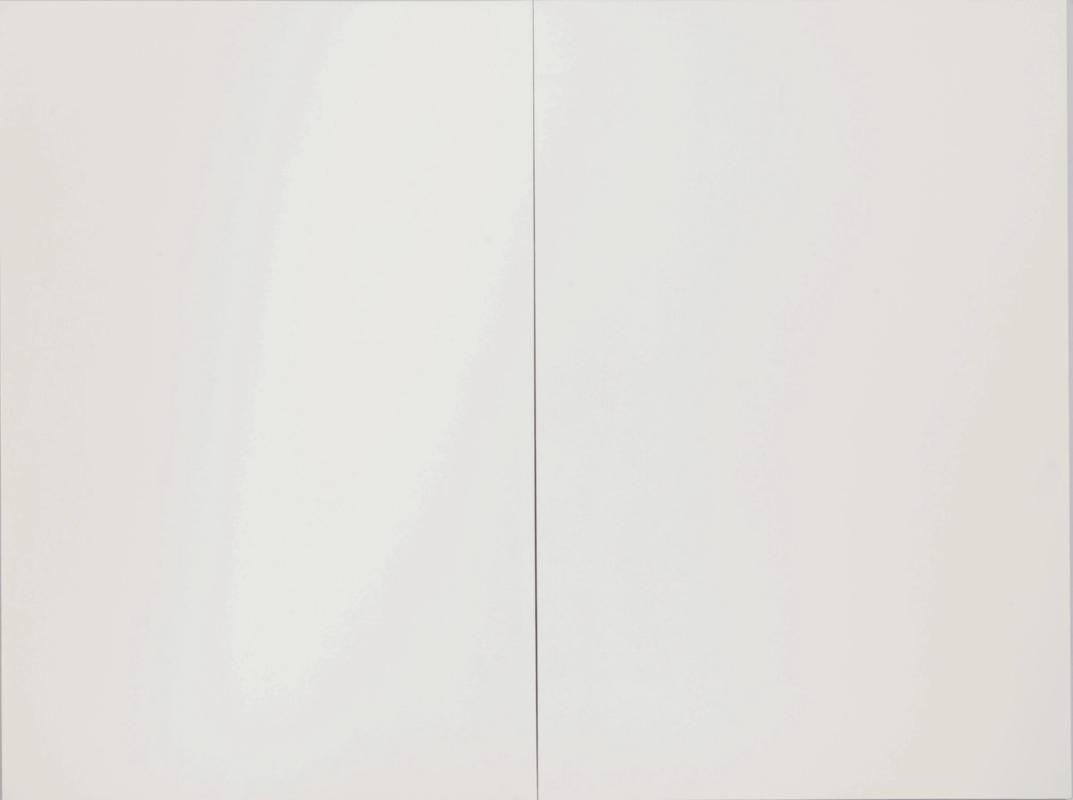

Robert Rauschenberg's White Paintings, created in 1951, represent a pivotal moment in 20th-century art, challenging traditional notions of painting and setting the stage for later movements such as Minimalism and Conceptual art. These works consist of modular canvases painted entirely white, designed to capture and reflect the subtle variations in light and shadow within their surrounding environment. The series included variations of one, two, three, four, five, and seven panels, each aiming to achieve a surface that appeared untouched by human hands, as if the paintings had arrived in the world fully formed (Rauschenberg Foundation).

Rauschenberg's approach to the White Paintings was radical for its time. He used basic house paint applied with a roller to achieve a uniform surface that acted as a responsive screen to ambient conditions, such as the flickering of light, shadow, and even the weather. Rauschenberg himself described these works as "clocks," suggesting that if one were sensitive enough, they could discern the number of people in the room, the time, and even the weather outside by observing the paintings. This interactive aspect of the White Paintings underscored Rauschenberg's interest in the role of the observer and the environment in defining the artwork's meaning (The Museum of Modern Art).

The White Paintings were influential in the development of John Cage's experimental music composition 4’33", where the absence of intentional sound invites the audience to listen to ambient noises occurring during the performance. Cage admired the White Paintings for their ability to register ambient events, a concept he echoed in his composition. The paintings, therefore, not only questioned the essence of visual art but also inspired cross-disciplinary influences in music and performance (Rauschenberg Foundation) (The Metropolitan Museum of Art).

Rauschenberg's White Paintings also embodied the idea that the creation process could be detached from the artist's hand. This concept was highlighted when Rauschenberg had Brice Marden, his studio assistant, repaint some of the panels for an exhibition in 1968, emphasizing that the artistic value lay not in the creator's physical act of painting but in the conceptual framework behind the work. This detachment from traditional authorship and the focus on conceptual integrity over technical execution would become central themes in later contemporary art practices (The Museum of Modern Art) (SFMOMA).

Through their simplicity and emphasis on perceptual nuances, the White Paintings challenge viewers to reconsider the role and definition of art. By reducing the painting to its most elemental form, Rauschenberg invites an engagement with the artwork that transcends visual aesthetics, opening a dialogue between the artwork, its environment, and its observers. These pieces not only reflect Rauschenberg's innovative spirit but also his profound influence on the trajectory of modern and contemporary art (Rauschenberg Foundation) (The Metropolitan Museum of Art).