Artists/Philip Guston

Fast Facts

Evolution from Realism to Abstract Expressionism

Guston began his career with a focus on realism and murals, inspired by the social and political issues of his time. He then shifted to Abstract Expressionism in the 1950s, becoming known for his lyrical, abstract style.

Return to Figurative Painting

In a notable shift in the late 1960s, Guston returned to figurative painting, which was at the time a radical move away from the dominant trends of abstract art. His later works featured cartoonish, grotesque figures and personal symbols.

Iconic Cartoon-like Imagery

His later works are characterized by a cartoon-like style, with crude, simplistic figures and objects, often depicted in a limited palette dominated by pinks, reds, and blacks.

Themes of Personal Struggle and Social Issues

Guston's art often reflects his personal struggles and comments on broader social and political issues, including reflections on identity, existential anxiety, and the human condition.

Thick, Expressive Brushwork

He is known for his heavy, expressive brushstrokes, which add a tactile, dynamic quality to his paintings.

Influences from Renaissance to Modernism

Guston's work shows influences ranging from Italian Renaissance painting to modernists like Picasso and de Chirico.

Symbolic Objects

His paintings often include a recurring set of symbols, such as shoes, clocks, cigarettes, and light bulbs, which serve as motifs throughout his work.

Biography

Philip Guston, originally born Philip Goldstein on June 27, 1913, in Montreal, Canada, was a transformative figure in 20th-century American art, whose career spanned several pivotal art movements. His journey from abstract expressionism to figuration and back marked him as a versatile and controversial artist.

Guston's early life was marked by hardship and tragedy. The youngest of seven children, his family moved to Los Angeles in 1919, fleeing the pogroms in Russia. His father struggled to find stable work, and the family encountered the growing influence of the Ku Klux Klan. A profoundly impactful moment in Guston's childhood was the suicide of his father, which he discovered, pushing him towards drawing and art as a means of escape and expression.

Guston's artistic journey began in earnest when he attended the Manual Arts High School in Los Angeles, where he met Jackson Pollock. Both were expelled for distributing a leaflet mocking the English department. Despite this setback, Guston was awarded a scholarship to the Otis Art Institute in 1930. His early works were influenced by his travels in Mexico and his exposure to the murals of prominent Mexican artists, which instilled in him a lifelong commitment to social and political themes in his art.

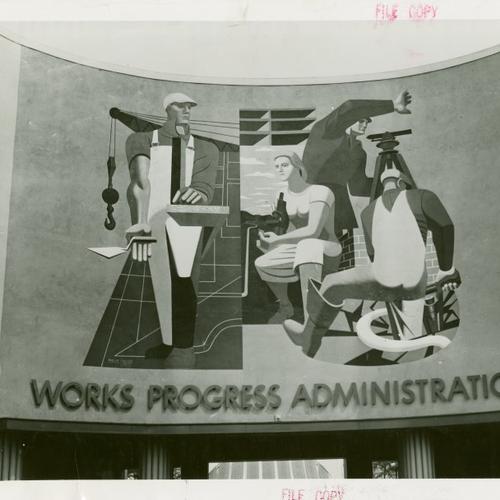

In the 1930s, Guston, then known as Philip Goldstein, engaged in political activism through his art, creating murals with anti-fascist themes, notably collaborating with Reuben Kadish and Jules Langsner on a mural in Mexico that depicted the struggle against terror. This work, alongside others commissioned by the WPA during the Great Depression, reflected his commitment to social issues and his admiration for Renaissance and Mexican muralists.

By the 1950s, Guston achieved recognition as a first-generation abstract expressionist, a movement he preferred to call the New York School. His works from this period, characterized by gestural strokes and a limited palette, placed him at the forefront of American art. However, by the late 1960s, disenchanted with the abstract movement and moved by the political turmoil in the United States, Guston returned to figuration, introducing a personal, cartoonish manner. This shift was controversial, with critics and peers alike questioning his new direction, which featured enigmatic hooded figures and stark, symbolic objects. Despite initial criticism, these works are now celebrated for their courageous commentary on social and political issues.

Guston's influence extends beyond his stylistic transformations, impacting future generations of artists. He showed that it was possible to bridge the gap between abstract and figurative painting, addressing profound social issues without sacrificing personal expression. Guston passed away on June 7, 1980, in Woodstock, New York, leaving behind a legacy that continues to inspire and challenge (Wikipedia) (The Art Story) (Encyclopedia Britannica).

Importance

Philip Guston's importance in the art world can be attributed to several key factors that have cemented his legacy as one of the most influential American painters of the 20th century:

Pioneering Shifts Between Styles

Guston is renowned for his audacious shifts in style, moving from figuration to abstraction and back to figuration. This fearless evolution showcased his commitment to personal expression over conformity to any single art movement, influencing future generations of artists to explore beyond the boundaries of established styles (The Art Story) (National Gallery of Art).

Social and Political Engagement

Throughout his career, Guston engaged deeply with social and political themes. His early murals addressed issues of racism and inequality, and his later works continued to probe societal issues, including the Vietnam War and the Holocaust. This aspect of his work highlights the power of art to comment on and engage with the world's tumult and injustices (National Gallery of Art).

Integration of Personal Symbolism

Guston's work is marked by the use of personal symbols, most notably in his late figurative paintings featuring hooded Klansmen. These figures were not direct representations of racism but served as a complex symbol of evil, self-examination, and the artist's contemplation of his role in a society rife with violence and bigotry. His ability to infuse his work with deeply personal and universally resonant symbols has been a significant influence on later artists (The Art Story) (National Gallery of Art).

Contribution to Abstract Expressionism

Guston was a key figure in the Abstract Expressionist movement, celebrated for his abstract works that emphasized the physical act of painting itself. His contributions to this movement helped solidify New York's status as a global art center in the mid-20th century. Guston's abstract works, characterized by their gestural brushwork and emotional intensity, remain a vital part of his legacy (The Art Story) (National Gallery of Art).

Legacy of Innovation and Influence

Guston's willingness to reinvent his artistic style and engage with difficult themes has left a lasting legacy. He demonstrated that an artist could successfully navigate between abstraction and figuration, challenging prevailing art world norms and expectations. His work has influenced a wide range of artists, from those interested in figuration to others drawn to the expressive potential of abstraction (The Art Story).

Technique

Philip Guston's painting technique evolved significantly throughout his career, reflecting his journey through different art movements and his personal exploration of themes.

Influenced by Social Realism

In his early years, Guston created murals that were socially and politically charged, influenced by the Great Depression and his own experiences with social injustice. These works, often created under the auspices of the WPA (Works Progress Administration), showed his commitment to portraying societal issues.

Detailed and Narrative-Driven

His murals were detailed, narrative-driven, and inspired by the works of Mexican muralists like David Siqueiros and Diego Rivera, as well as by the Renaissance masters such as Piero della Francesca and Paolo Uccello. Guston's work during this period was marked by a strong sense of realism and a commitment to social commentary (The Art Story) (Wikipedia) (National Gallery of Art).

Gestural Brushwork

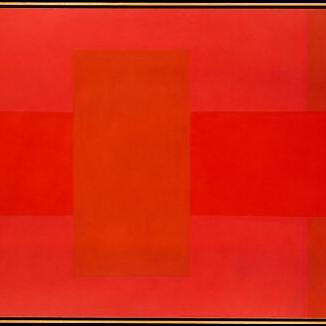

During his phase as an abstract expressionist, Guston's technique was characterized by gestural brushwork and a focus on the physical act of painting. This period marked a significant departure from his earlier, more figurative work.

Limited Palette

He favored a limited palette during this period, predominantly using black, white, grays, blues, and reds, which helped to concentrate the viewer's attention on the texture and movement of the paint itself (Wikipedia).

Cartoonish Figures and Objects

In the late 1960s, Guston returned to figuration, adopting a unique, cartoonish style. This late period is characterized by simplistic, almost child-like figures, including the recurring motif of hooded Klansmen, which he used to explore themes of evil, morality, and social commentary.

Thick, Impasto Paint

Guston used thick, impasto paint to give his works a tactile, almost sculptural quality. This technique allowed him to build up surfaces and create a sense of depth and dimensionality in his paintings.