Joan Miró's period from 1927 to 1937, termed as his phase of "Painting and Anti-Painting," is one of the most innovative and rebellious spans in his artistic journey. Kicking off with his bold declaration to "assassinate painting," Miró embarked on a decade-long exploration that challenged the conventional boundaries and practices of painting. This era is a testament to his desire not just to negate painting as a form but to reinvigorate and redefine it through radical approaches and techniques (The Museum of Modern Art).

Miró's experimentation during these years was deeply influenced by the socio-political upheavals of his time, including the rise of Fascist regimes in Europe. His work from this period is characterized by the use of collage, distortion of figures into grotesque forms, and the application of acidic, hallucinogenic colors. Such elements contributed to a body of work marked by its heterogeneity and predicated on a principle of difference that questioned and expanded the notion of what painting could be (The Museum of Modern Art).

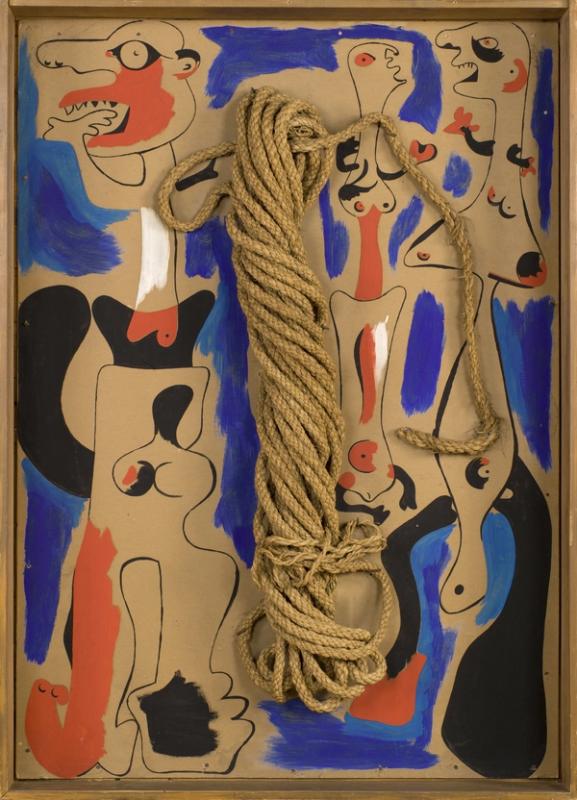

The use of unconventional materials and the integration of ready-made objects into his work allowed Miró to push the limits of traditional painting. His figures during this time often veered into the monstrous, underlining his departure from more lyrical, surrealist expressions to something more critical and engaged with the materiality of his art. This period also saw Miró constructing a deliberately diverse array of works, challenging the viewer's expectations and redefining the essence of painting itself (The Museum of Modern Art).

Miró's earlier works leading into this phase, such as "Dog Barking at the Moon" (1926) and "Dutch Interior (I)" (1928), already hinted at his growing interest in transforming the art of painting. These works demonstrated his capacity for innovation and his willingness to explore new forms and expressions, setting the stage for his later experiments in anti-painting. "Dog Barking at the Moon" represents a surreal, yet playful approach to painting, incorporating symbols and forms that blur the line between reality and imagination. "Dutch Interior (I)," on the other hand, showcases Miró's engagement with reinterpretation and distortion of classical artworks, in this case, transforming a genre painting into a vibrant, abstract composition (The Art Story).

Throughout this transformative decade, Miró remained deeply engaged with the challenges of his time, both artistically and politically, using his work as a means to explore and question the very nature of painting. His efforts to "assassinate painting" thus reflect a complex interplay between destruction and creation, between the negation of traditional forms and the search for new, radical ways of expression. This phase of Miró's work underscores his profound impact on the course of modern art, highlighting his role not just as a painter, but as a visionary who continuously sought to redefine the boundaries of his medium.