Helen Frankenthaler's soak-stain technique emerged in the early 1950s as a groundbreaking approach that bridged the gap between Abstract Expressionism and Color Field painting, setting the stage for a new direction in abstract art. This technique, pioneered by Frankenthaler in her seminal work Mountains and Sea (1952), involved diluting oil paint with turpentine or kerosene and pouring it onto unprimed canvas, allowing the paint to seep into the weave of the canvas. The effect created was of ethereal, amorphous landscapes of color that appeared to be one with the canvas, rather than sitting atop it (invaluable.com).

Frankenthaler's education at Bennington College under Paul Feeley, and her encounters with leading figures of the New York art scene, such as Jackson Pollock, Lee Krasner, and Willem de Kooning, through art critic Clement Greenberg, deeply influenced her artistic development. By the 1960s, Frankenthaler had solidified her position in the art world with major retrospectives at the Jewish Museum and the Whitney Museum of American Art, showcasing her evolution and experimentation across mediums, including her significant contributions to printmaking and woodcuts (invaluable.com).

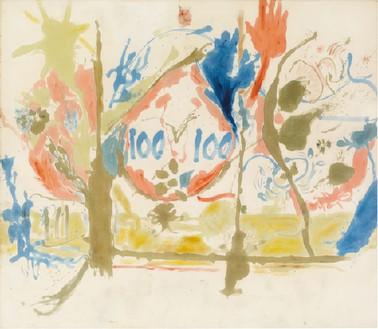

The soak-stain technique not only differentiated Frankenthaler from the gestural brushwork of her Abstract Expressionist predecessors but also allowed her to explore the natural landscape as a primary source of inspiration. Unlike the existential and sublime pursuits characteristic of first-generation Abstract Expressionists, Frankenthaler's work was rooted in a profound engagement with the physical world, manifested through vibrant color washes and vast, fluid landscapes (invaluable.com).

During the summers of the 1950s and 1960s, Frankenthaler's time in Provincetown, Massachusetts, further influenced her artistic approach, encouraging experimentation with enamel paints and later, solvent-based and water-based acrylics. This period marked a significant exploration of scale, process, and the interplay between painted and unpainted canvas, allowing Frankenthaler to articulate space through color and form in innovative ways (invaluable.com).

In the later stages of her career, particularly in the 1970s, Frankenthaler's experimentation extended into the medium of woodcut, where she applied her signature blending of colors and forms. Collaborating with ULAE (Universal Limited Art Editions), she developed techniques that transformed the woodcut medium, paralleling the fluid and vibrant qualities of her paintings. Works such as Madame Butterfly (2000) stand as testaments to her ability to adapt and innovate across different artistic mediums (invaluable.com).

Frankenthaler's legacy is complex, shaped not only by her artistic innovations but also by the gender dynamics of the art world. Despite distancing herself from feminist discussions, her role as a female artist in a predominantly male Abstract Expressionist movement, and later in the Color Field painting movement, challenges contemporary readings of her work and its reception over time. Today, the market for Frankenthaler's work reflects a growing recognition and appreciation of her contributions to modern and contemporary art, evidenced by significant sales and the continued interest in her expansive oeuvre (invaluable.com) (The Art Story)