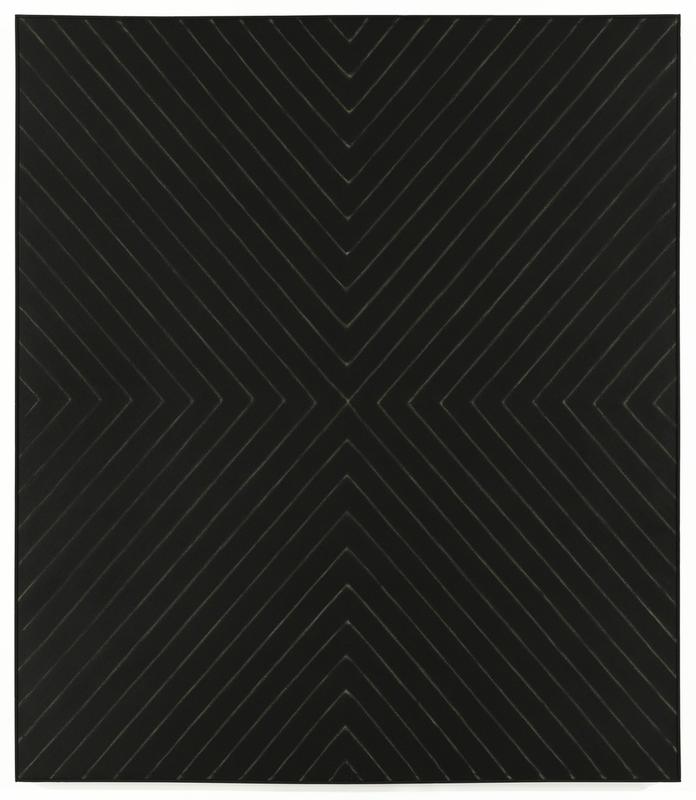

Frank Stella's "Black Paintings" series, created between 1958 and 1960, marked a significant departure from the abstract expressionism prevalent at the time and positioned Stella as a pioneering figure in minimalist art. Upon his arrival in New York City in 1958, Stella began this series, which rapidly garnered attention and acclaim. These paintings were characterized by their use of black enamel house paint applied with a roller over penciled lines on blank canvases, creating a series of parallel stripes separated by thin strips of unpainted canvas. This method emphasized the physicality of the painting process and the material aspects of the work (UO Blogs).

The "Black Paintings" were notably devoid of any illusion of depth or narrative, focusing instead on the painting as an object. This approach was underscored by Stella's use of symmetrical compositions, which played a crucial role in subverting spatial illusions, a technique used throughout the series. These works were not only a response to the subjective decision-making prevalent in the art of the time but also an exploration of non-compositional abstraction, where the emphasis lay on the materials and the viewer's engagement with the painting. Stella's famous statement from a 1964 interview, "What you see is what you see," encapsulates the essence of these works, highlighting their straightforward, minimalist nature (Phaidon).

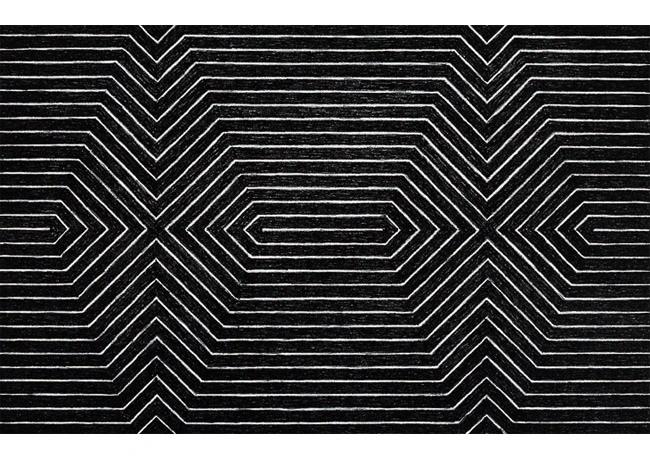

One of the most notable pieces from this series, "The Marriage of Reason and Squalor, II" (1959), exemplifies Stella's minimalist approach. This painting, which was included in the Museum of Modern Art's landmark exhibition "Sixteen Americans" in 1959, features two identical sets of concentric, inverted U-shapes composed of black enamel paint. Stella's application of paint directly onto the canvas, freehand, and his use of commercial black enamel paint emphasized the painting's two-dimensionality and its existence as a physical object rather than a window into an illusionistic space (The Museum of Modern Art).

The "Black Paintings" not only established Stella's reputation as a leading figure in minimalism but also served as a foundational moment in the history of modern art. Their influence is seen in the way they challenged and expanded the boundaries of painting, setting the stage for Stella's continued evolution and experimentation with color, shape, and form in his subsequent works. These early minimalist pieces remain pivotal, not just for their aesthetic and conceptual rigor but also for their role in the broader narrative of 20th-century art.