Artists/Claes Oldenburg

Fast Facts

Large-Scale Public Sculptures

Oldenburg is famous for his colossal public sculptures. These works often depict everyday objects, such as clothespins, shuttlecocks, or spoons, transformed into massive, playful installations.

Soft Sculptures

In the 1960s, Oldenburg began creating "soft sculptures" made of fabric. These works often represented mundane objects like hamburgers, typewriters, or telephones, rendered in soft, pliable materials that contradict their typical hard, functional nature.

Pop Art Influence

As a prominent figure in the Pop Art movement, Oldenburg's work is characterized by its whimsical and ironic approach to consumer culture and everyday items. His art often blurs the line between the ordinary and the absurd.

Collaborations with Coosje van Bruggen

Many of Oldenburg's large-scale sculptures were created in collaboration with his wife, Coosje van Bruggen. Their partnership led to the creation of iconic public artworks installed in various cities around the world.

Use of Scale and Material

Oldenburg's art is notable for its use of scale and unexpected materials, challenging viewers' perceptions of the familiar. By enlarging, softening, or otherwise distorting common items, he invites a reexamination of their form and function.

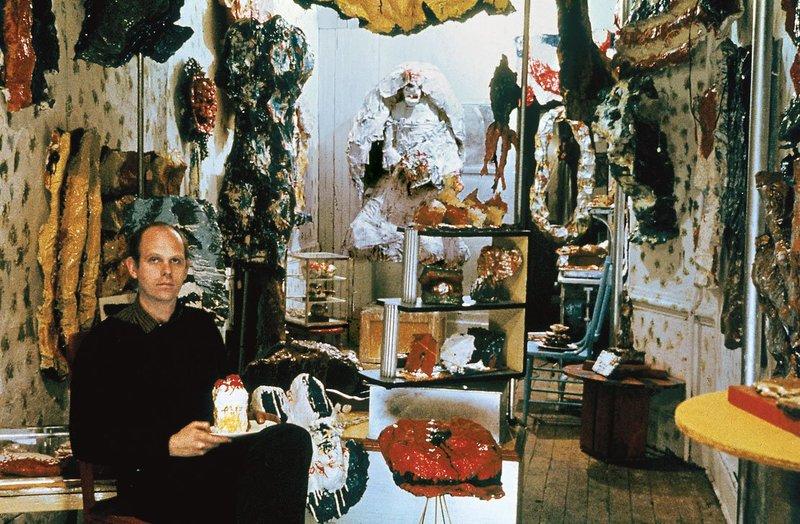

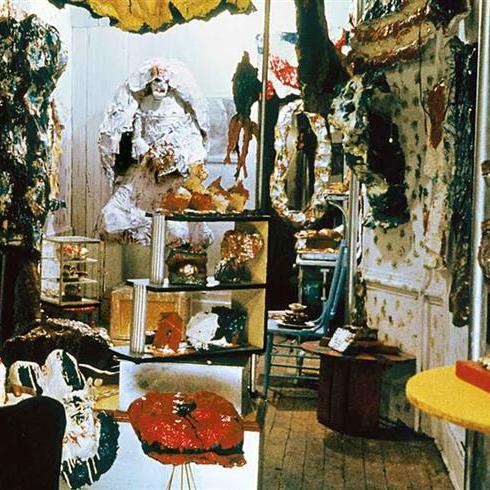

The Store and Early Performances

Early in his career, Oldenburg ran a storefront in New York where he sold plaster sculptures resembling food and other merchandise, blurring the line between art and commerce. This period also included performance art elements.

Biography

Claes Oldenburg, a pivotal figure in the Pop Art movement, was born in Stockholm, Sweden, on January 28, 1929, and passed away on July 18, 2022, in New York City, U.S. Oldenburg's upbringing was international, spending his early life in the United States, Sweden, and Norway due to his father's career as a Swedish consular official.

His formal education was at Yale University from 1946 to 1950, initially focusing on writing before transitioning to art. After working as an apprentice reporter in Chicago, Oldenburg attended the School of the Art Institute of Chicago from 1952 to 1954, becoming a U.S. citizen in 1953 (Encyclopedia Britannica).

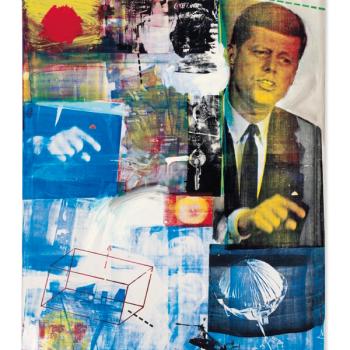

Oldenburg moved to New York City in 1956, where he immersed himself in street life, drawing inspiration from store windows, graffiti, advertisements, and trash, which led him to shift his artistic focus from painting to sculpture. This period marked the beginning of his exploration into soft sculptures and the use of everyday objects as subjects, hallmarks of his contribution to Pop Art. His early works included "The Store" (1960-61), a collection of painted plaster copies of everyday items, and a series of "happenings," experimental presentations involving sound, movement, objects, and people (Encyclopedia Britannica).

His association with the Pop Art movement in the 1960s brought him into the limelight, with performances dubbed "Ray Gun Theater" and his significant shift towards sculptures made from materials like plaster-soaked canvas and enamel paint, depicting commonplace objects. Oldenburg's "The Store," a month-long installation stocked with sculptures resembling consumer goods, and his creation of giant soft sculptures, like an ice-cream cone, hamburger, and a slice of cake, showcased his brash and humorous approach to art, challenging the prevailing abstract expressionist period (Wikipedia).

Throughout his career, Oldenburg's large-scale sculptures of mundane objects often elicited initial ridicule before gaining acceptance and popularity. His works like "Lipstick (Ascending) on Caterpillar Tracks" (1969) exemplify his penchant for blending whimsical imagery with social and political commentary. From the early 1970s, Oldenburg concentrated almost exclusively on public commissions, with notable collaborations with his wife, Coosje van Bruggen, enhancing his legacy within the art world (Wikipedia).

In his later works, Oldenburg's approach became more abstract, conceptual, and site-specific, engaging directly with the viewer's perspective and the spaces they inhabited. For example, "Stake Hitch" (1984) challenged viewers' perceptions within The Dallas Museum of Art with its illusionistic elements, demonstrating Oldenburg's continued innovation in sculptural form and thematic exploration (The Art Story).

Oldenburg's childhood and education, marked by an international upbringing and a broad academic background, deeply influenced his artistic trajectory. His move to New York in the 1950s, immersion in the city's vibrant street culture, and the influence of the Lower East Side's artistic community were pivotal in shaping his unique artistic voice. This blend of experiences fostered Oldenburg's distinctive approach to art, characterized by a playful yet critical interrogation of everyday objects and consumer culture, positioning him as a key figure in the Pop Art movement and beyond (The Art Story).

Series

-

The Street

1960

-

The Store

1961

-

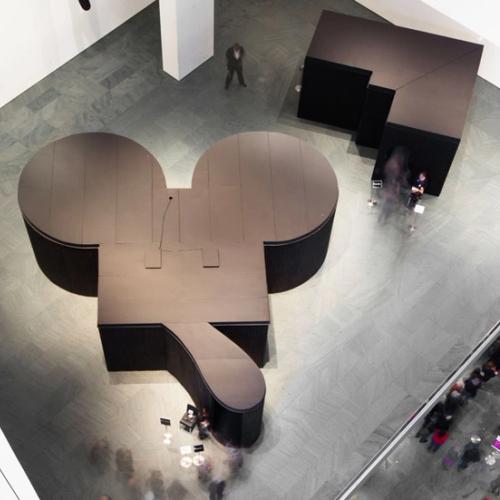

Mouse Museum/Ray Gun Wing

1965–1967

-

Geometric Mouse

1969–1971

-

Monumental Sculptures

-

Typewriter Eraser

-

Spoonbridge and Cherry

-

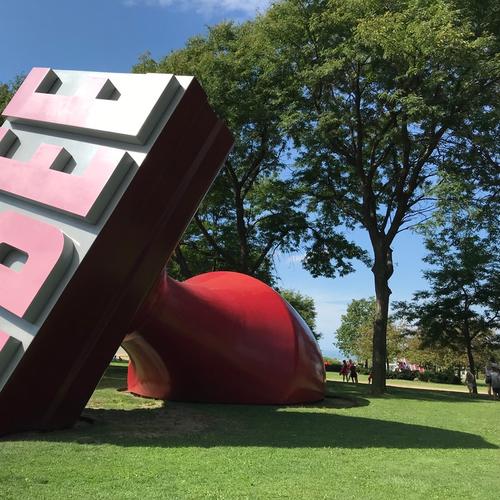

Apple Core

-

Shuttlecock

-

Saw, Sawing

-

Matches

-

Clothespin

-

Shovel

-

Free Stamp

-

Big Sweep

-

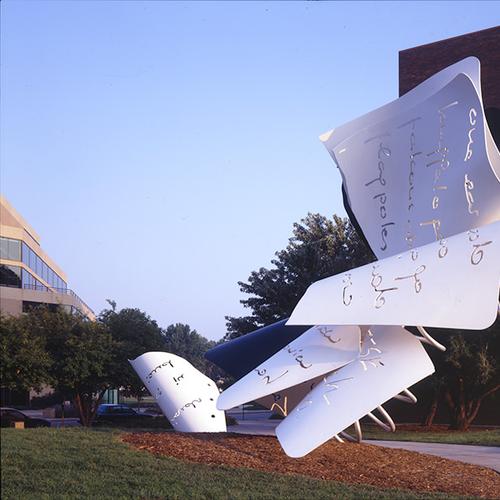

Torn Notebook

-

Swiss Army Knife

-

Pickaxe

-

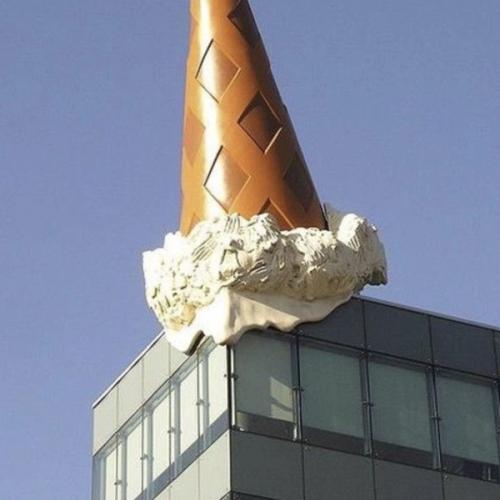

Ice Cream Cone

-

Safety Pin

-

Paint Brush

Importance

Claes Oldenburg's significance in the art world is deeply rooted in his transformative approach to sculpture, his pioneering role in the Pop Art movement, and his impact on public art and urban spaces.

Pioneer of Pop Art

Oldenburg distinguished himself from his contemporaries through his innovative large-scale sculptures of everyday objects. Unlike many of his Pop Art peers, Oldenburg's works often carried clear social and political messages, such as his anti-war stance during the Vietnam War era, exemplified by "Lipstick Ascending on Caterpillar Tracks" (The Art Story).

Democratizing Art

Oldenburg’s radical upscaling of mundane objects challenged traditional notions of sculpture and brought art closer to everyday life. His works, such as the iconic "Clothespin" and "Spoonbridge and Cherry", became landmarks in public spaces, making art accessible to a wider audience and integrating it into the fabric of everyday life (Smithsonian Magazine).

Innovative Use of Materials and Scale

Oldenburg was renowned for his inventive use of materials and his explorations of scale. His early works included soft sculptures made from canvas or vinyl filled with foam, pushing the boundaries of sculpture as a medium. This innovative approach extended to his monumental public sculptures, which played with the scale of familiar objects to challenge viewers' perceptions and engage them in a new form of interaction with art (Smithsonian Magazine).

Impact on Public Art

Oldenburg's work has had a lasting impact on the concept of public art. His sculptures, often placed in highly visible urban locations, have become integral parts of their environments, serving as gathering points and landmarks. Through his art, Oldenburg advocated for the idea that art should live among people, be accessible, and resonate with the everyday lives of its audience. His belief that art should not be confined to galleries or museums but instead be an active part of community life has influenced subsequent generations of artists and city planners alike (Smithsonian Magazine).

Legacy and Influence

The impulses that Oldenburg tapped into with his work are now pervasive in the field of art. It’s hard to overstate his radical approach and how it paved the way for contemporary artists to explore similar themes and methodologies. His legacy is visible in the widespread acceptance and incorporation of everyday objects and pop culture references in art, extending the legacy he established (Smithsonian Magazine).

Technique

Claes Oldenburg's artistic technique is distinguished by its innovative approach to sculpture, bridging pop art sensibilities with a deep engagement in material experimentation and scale manipulation.

Soft Sculptures

Oldenburg's shift from hard to soft materials in the early 1960s marked a radical departure in sculpture. He created limp, deflated forms that contrasted traditional solidity, introducing a sense of gravity and chance to his pieces. His soft sculptures, often depicting everyday objects like clothespins and light switches in exaggerated scales and abstract forms, were made from materials such as vinyl, canvas, and later, more sophisticated fabrics filled with foam or other soft materials. These works challenge our perceptions of ordinary items by distorting their functionality and scale (Pulitzer Arts Foundation).

Collaborative Process

From the mid-1970s onwards, Oldenburg often collaborated with his wife, Coosje van Bruggen. This partnership expanded his scope into monumental public sculptures, integrating Van Bruggen's insights from art history and criticism. Their collaborative works continued Oldenburg's exploration of everyday objects but on a much grander scale, often incorporating elements of humor and whimsy (Artland Magazine).

Monumental Sculptures

Oldenburg's large-scale public sculptures are perhaps what he is most renowned for. These works magnified everyday items to an imposing scale, transforming them into iconic landmarks within urban spaces. The technique behind these monumental sculptures involved meticulous planning and fabrication processes, often in collaboration with engineers and fabricators, to ensure their structural integrity while maintaining the playful essence characteristic of Oldenburg's vision. The materials for these giant sculptures varied depending on the specific requirements of each project but often included metal, fiberglass, and other durable materials to withstand outdoor environments (Artland Magazine).

Drawing and Planning

Integral to Oldenburg's technique was his practice of drawing and making collages as a primary method of conceptualization. These preparatory works were vital in the planning of both his soft sculptures and his monumental public artworks. His drawings not only explored the visual aspects of his ideas but also served as a laboratory for investigating the physical and spatial dynamics his sculptures would encounter in both gallery and public settings (Artland Magazine).

Elimination of Gestural Brushwork

Unlike many of his contemporaries in the Abstract Expressionist movement, Louis eschewed overt gestural brushwork, instead favoring a method where the hand of the artist was not directly visible. This approach aligns with his interest in purity and abstraction, where the focus is on color and form rather than on the physical action of painting. By removing the trace of the artist's hand, Louis sought to achieve a kind of universality, allowing the viewer to engage more directly with the work's visual and emotional content (National Gallery of Art).